The crew of a U.S research base in the Antarctic are attacked by members from the neighbouring Norwegian camp. Bemused by the attack, the research base and its crew become the unwitting host to an alien creature able to mimic any life form and driven by its own survival. Vilified by contemporary critics, The Thing remains one of John Carpenter’s best works and a staple of the horror genre, still played across cinemas every Halloween.

Adapted from the novella Who Goes There? John Carpenter’s sixth film is a confluence of Carpenter’s own style and other influences. The frigid confines of the U.S research base bears the cold claustrophobia of The Outlook Hotel; the central location of Stanley Kubrick’s’ The Shining. Instead of building towards a terrifying culmination as The Shining does, The Thing unfolds unreal time, the days marked by establishing shots of the research base as panic and horror sets in. Located in the dark corners of the Antarctic as men battle an unspecified monster, The Thing walks in the shadow of H.P. Lovecraft and his story, At The Mountains of Madness. Shades of Ridley Scott’s Alien also trickle into The Thing . Both films share the premise of a ragtag crew whose mundane routine is upended by an alien encounter. Despite its mixed parentage, The Thing is undeniably a Carpenter creation. Eerie P.O.V shots and long takes which hallmarked Halloween reappear while a synthetic score permeates The Thing as it splices with classical overtures. A thread of dry humour, prevalent in Escape From New York, appears throughout The Thing despite its mounting horror.

Going mad together

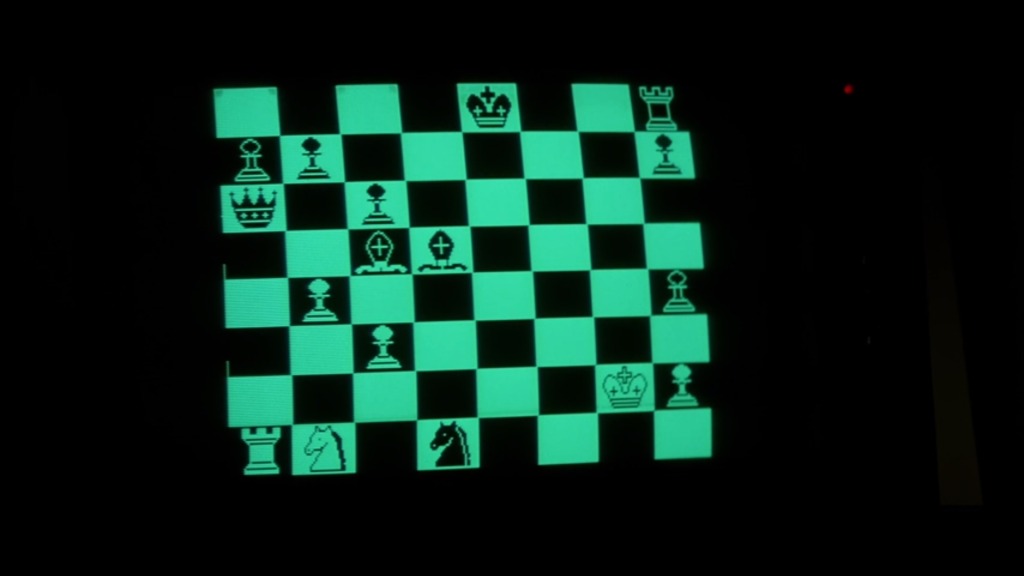

The Thing makes it plain that nothing is right from its beginning. The characters who populate the base, much like The Shining’s Jack Torrance, are already at breaking point. The crew members of the research base all appear under the spell of cabin fever. MacReady wrecks his chess computer upon losing to the machine while others nonchalantly gawk at the crazed Norwegians. Divisions are all too apparent among the crew. After The Thing’s opening, the older generation clash with the youngsters among their team; their quiet card and pool games a stark contrast to the casual dope smoking of their successors. The working-class support staff are distinguished visually from the more refined research staff while the pilots and security crew exude a tight self restraint.

The research base of The Thing is already a tinder box, and the monster is the light. Alerted to the thing’s presence, the crew become completely corrupted by paranoia. Every act by another, however minor, may be genuine, the thing in disguise, or a person cracking under the pressure. The confusion is compounded by the camera’s unreliable narration. The camera begins with a degree of objective detachment, distantly observing the Norwegians while cutting to a medium close-up of the fleeing husky, highlighting that something is not right with this situation. Yet Carpenter’s use of point of view upends all trust in the camera. Once calm is relatively restored and a few men go to investigate the Norwegian camp, Carpenter switches to a first-person perspective. Slowly proceeding through the quiet research facility, the camera becomes the creature, skulking through its surroundings until resting on the husky, now rescued from the Norwegians and within the facility. The audience becomes submerged in the paranoia as subsequent clues could be real or the fear induced sights of crew men pumped by adrenaline and fatigue. The creature itself becomes lost in the mayhem, its progression from one imitation to another becoming deliberately obscured while it increasingly manipulates events.

A slow thaw

The Thing is not driven by the spectacle of its central monster. A broader story, in which the mythos of the shape-shifting creature is couched, slowly emerges from the film’s cold surroundings. The story’s development is remarkably grounded, built upon fragments as the crew investigate the creature. The narrative splits between the crew and the creature as it actions are uncovered or it is caught. The narrative fractures further as the crew turn against each other. Crew members uncover clues about the alien and the danger it poses but, wracked by fear, do not share their knowledge with each other. Echoing MacReady’s lost game of chess at The Thing’s beginning, the crew find themselves in a one-sided game against a far greater, and far more dangerous, intelligence. The Thing follows the pattern of a chess match, with move and counter move between the crew and the creature. At each new step, the two sides take more extreme measures to ensure their success. The slow ratcheting of the stakes at play is layered with foreshadowing as the actions once considered crazy become the most viable options.

The Thing’s deliberate confusion over events begins to clear upon a second viewing. Incongruous details and unexplained scenes collect into a clearer narrative. The hero-figure also shifts from the gruff young pilot MacReady to the reserved Dr. Blair. The Doctor is the first to understand how the creature operates, the consequences of its existence and most importantly, where the Norwegians went wrong. Although MacReady may deliver the physical combat against the thing, it is Blair’s intelligence which offers hope for stopping the creature. Understanding Blair’s motives during the second act of The Thing makes his character arc that more tragic upon revisiting the film. For first-time viewers who may be inured by more recent horror films, The Thing works equally well as a thriller; a complex murder-mystery in which the killer really could be anyone.

Making a monster

The greatest element of The Thing is its design. From Halloween and throughout his work in the 1980’s, Carpenter had a clear visual watermark of long panning takes, P.O.V shots, alongside the extensive use of shadow and synthetic scores. The film also benefits from great practical effects and a team of producers, editors, photographers and designers who often joined Carpenter across multiple films. The documentary, The Making of The Thing , is a useful source for the practical history of The Thing. Alongside Carpenter’s regular crew is Rob Bottin’s work on the creature itself. Encompassing one-tenth of The Thing’s fifteen-million-dollar budget, Bottin had a bold vision of the creature as an amalgamation of multiple life-forms, both terrestrial and alien. Subjecting himself to a gruelling schedule, Bottin’s creations define The Thing. Intricately grotesque, the creature’s appearances were removed from the typical horror trope of the monster being, as Carpenter says, “just a guy in a suit”. The decades may have passed but the monster’s rubbery appearance and animations make the creature only seem more unearthly.

Beyond the monster, the reliance on practical effects and the creativity of the effects team have preserved The Thing. From the use of models to matte paintings, The Thing marks a zenith of what practical effects are able to achieve. Throughout the twilight period of the 1970s and 1980’s; from The Thing to Blade Runner, films were created which remain visually impressive to this day without computer graphics. It is a mantle which contemporary directors, such as Denis Villeneuve and Christopher Nolan have fortunately taken up in big budget cinema. Perhaps my favourite visual effects during The Thing are the moments when the creature is caught mid-transition, with simple prosthetics upon one of the crewmen blurring the line between the normal and the alien. The Thing also resonates in the mind due to its soundscape. The score by Ennio Morricone haunts the film, its thudding beat invoking the patient stalking by the creature. Besides Morricone’s score, the sound design is equally spectacular. The bellows and screams of the creature eerily invoke the sounds of a cornered animal, viscerally connecting with the audience as it fends off the crewmen.

The right team

The casting of The Thing was a perfect fit for the film. Carpenter involved Kurt Russell early in the Thing’s development to help with the film’s creation, but Russell was the last actor to be selected for a role. Each actor breathes life into their character, providing a subtle yet clear distinctiveness to this odd assortment of persons living at the edge of the world. The absence of women unintentionally reinforces the crew’s existence at the strained edges of society. The believability of the cast’s performance comes from their extensive time on set in Alaska and Canada. According to Richard Masur who played the dog handler Clark, the cast spent two weeks together on location before filming to work out the dynamics across the research crew. This preparation pays off when viewing The Thing, as fault-lines within the crew organically appear from the beginning.

The Thing remains among Carpenter’s best works and will always be a favourite of mine as Halloween nears.

By Saul Shimmin

For the trailer, see below: